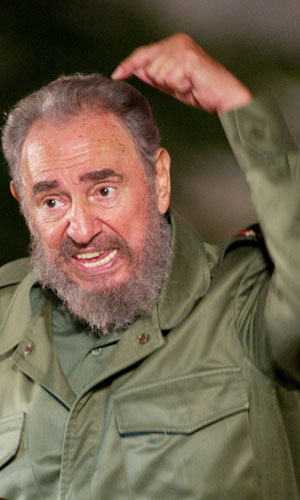

Photo:Emad Bornat, Foix, France, November 2007./Patrick Chalmers

I thought that headline might be the best angle for a hard news story to capture the tale of Emad Bornat, a Palestinian cameraman I met the other day near where I live in France. Emad was the story’s sometime stringer and “nobody” while Reuters was to play the part of big bad media. But then I hesitated for reasons some people, not least fellow journalists, might criticise.

Emad has been hit by rubber bullets, arrested and beaten while covering protests against Israel’s illegal land seizures in the West Bank. Last year he spent 60 days in jail and under house arrest awaiting charge for alleged violent acts against Israeli border guard. Since then, he says, Reuters has put him on hold, failed to renew his press card and denied him any form of compensation for the time of his detention.

I checked out what he said informally with Reuters but stopped short of going straight off for an on-the-record response from my former employers. Time will tell whether I was right to tackle the issue directly with them instead of trumpeting it via other media.

The reason I met Emad in the first place was that he was being interviewed on Radio Transparence about his film Bil’in against the Wall, which tells of his village’s non-violent campaign to reclaim its land. I went along as the programme’s English/French interpreter.

Emad impressed me deeply with his commitment to journalism and his faith in the power of video pictures to present the truth and to prevent injustices against the innocent. He became a cameraman only in 2001, after losing his gardening job in the second intifada, when he could no longer cross the border to work in Israel. By 2005 he was stringing for Reuters, feeding them footage as Bil’in came to symbolise Palestinian protests about the Israeli separation wall.

Photo:Four maps show (L to R) Palestinians’ loss of land to Israel from 1946 to 2006./Patrick Chalmers

The 36-year-old was arrested in November 2006, accused of throwing stones at a border guard with one hand while filming him with the other. Emad had a head wound that needed several stitches by the time he arrived under army escort at the nearest police station. Officers escorting him in a jeep said a radio set fell on him.

He was held in prison for 20 days and under house arrest for a further 40 before being freed on bail of nearly $4,000. His case remains pending. He told me Israeli soldiers had beaten him while he was under arrest, pointing to a scar under his left eye. “They took my camera and they beat me, the Israeli border guards,” he said.

I’d watched Emad’s film on the net before meeting him. I began by wondering at the futility of wave after wave of demonstrations over a series of weeks. As a political activist myself, a claim I’m almost embarrassed to make when I see the commitment of those in the film, it made me chew over the eternal “what’s-the-point?” question. Yet the imagination, passion and sheer persistence of demonstrators’ non-violence, just by themselves, taught me a real lesson about taking action in the face of apparent hopelessness.

Again and again they approach the barrier cutting them off from their land only to be repulsed by soldiers firing rubber bullets and percussion grenades. Particularly striking was the image of one man’s impassive face, shown in close up as he lay prone in the dirt with Israeli soldiers pinioning his arms behind his back.

Emad, the father of four boys aged between three and 12, is an able ambassador both for his village and his chosen craft as a journalist. He doesn’t stop his children going to the regular protests after Friday prayers, where he often films.

“It’s dangerous for them but they want to go. All the kids from Bil’in they want to go,” he told me after the radio interview.

“I film my kids, I film my brothers in the protests. Many times they beat my brothers. My brothers were arrested by the Israeli army and I kept filming [knowing] I cannot do anything for them. With my camera I can protect them, to show the reality of what’s happening.

“In the Israeli court, the soldiers can lie, they say they threw stones. With my filming, I can show the truth.”

A genuine example of good journalism’s power to influence, something beyond the celebrity fests and PR puffs that pack out most media space.

Yet Emad has barely worked since his arrest more than a year ago. He says Reuters backed away from him – saying they said they didn’t want more trouble with Israeli authorities.

He still posts stuff on YouTube, so it gets a limited airing, but he can’t feed his family or buy equipment with page views.

His position, as a stringer rather than salaried staff, puts him in the shaky employment world of those doing most of the dangerous work for international media companies such as Reuters. These people, usually low-paid locals, not only pass where their generally white, male employers cannot, they’re often far more knowledgeable about the story and all its subtleties.

I had thought to write about Emad’s plight for a UK publication such as the Guardian or at least a trade publication such as the UK Press Gazette or the NUJ’s in-house magazine The Journalist.

I haven’t done yet for various reasons, not least of which is that one of the Reuters staff involved is a very good friend. I am also reluctant to profit from the story of someone I may or may not help by writing it. More fundamentally though, which surprises me given my usual conviction about journalism’s potential to influence, I’m not sure if a journalistic approach would be in Emad’s best interests.

“Big media screws small nobody” might make a decent enough, if fairly predictable, story. But it would also distract from the main story affecting Emad and his fellow villagers, which is Bil’in’s loss of territory and the bigger picture of Israeli-Palestinian conflict. My dilemma begs the question of whether journalists should always publish and be damned or sometimes hold their tongues and allow calmer reflection in private. I hope my instinct proves right.

So I’ve written this blog entry as a public record and passed an email with Emad’s detailed comments to Reuters bureau chief for Israel and the Palestinian Territories, Alastair MacDonald. I hope that they can sort something out between themselves, so that Emad can keep on doing his work. We’ll see.

Object lesson in engaging thoughtful brain before acting withless-than-thoughful fingers on keyboard.

There are some very damning criticisms around the film Darwin’s Nightmare, in French for example here and an English one here. I was going to look them up before tonight’s screening. I should have done so before posting here. Oops, my apologies. What I thought was a searing example of global capitalism is probably more like a rather tawdry example of dishonest film making – not quite such a momentous subject.

The points about money, I would still recommend.